Juice

Juice Store is a Hong Kong-based multi-brand streetwear retailer with a twenty-year legacy and a sturdy digital presence. Replete with a healthy list of brands—among them, Sacai, Nike, Undercover, and Needles—Juice Store wanted to cultivate a stronger point of view around culture at large.

I developed a series of content pillars, pitched and wrote feature articles, and steered brand voice for their editorial platform.

The Impermanent Spectacle: NYC’s Area Nightclub (1983-1987)

If you want to observe decadence in 2018, you might go on Instagram and peruse the foot fetishist’s hashtag “#grail”. There, resides the meaning of ‘podiatric capitalism’, if such a thing existed: flashy, maximal, insular, ephemeral. It’s a similar recipe to that of downtown New York’s nightclub, Area—except Area targets the whole body.

Area, half party, half prodigious art rotisserie, propagated decadence between the years 1983 and 1987. Each affair was an immersive microcosm of excess, regularly luring guests like Grace Jones, David Byrne, Cher, Madonna (a recently ‘discovered’ and newfound fixture of the downtown scene), John F Kennedy Jnr. and… well, just Google it. The crowd at large was a spectacular mix of salty downtown kids, manicured uptown folk, the utterly elite and the lowly clingers-on—preening your feathers and actually entering Area were two very different things. Impatient maybe-guests would spill across the TriBeca street, packed tightly together like anthropomorphic sushi rice. “To not get in is to die,” expresses a guest in the book AREA: 1983-1987. She lived, “thanks to her ostrich-feathered turban.”

“People always measure the success of a thing by its longevity,” says Eric Goode, Area’s co-owner, “but the entire point of Area was its impermanence.”

The enormity of Area’s, ahem, area made the scope for art and installation near-boundless, with Chuck Close, Andy Warhol, Jean-Michel Basquiat, Claes Oldenburg, Ed Kienholz and pop purveyors Robert Rauschenberg and Tom Wesselmann holding indelible spots in the club’s history. Every six-ish weeks its owners—four guys from California: Eric and Christopher Goode, Darius Azari and Shawn Hausman—would exenterate the 13,000 square foot Hudson Street space spanning almost an entire block, fashioning a new space entirely. New York Magazine’s March 1985 issue describes the routine transformation as an ‘assault’. The publication chronicled one particular overhaul costing $60,000 (a paltry figure that would be in the hundreds-of-thousands today): “The flaming cross, the central artefact of December’s Faith theme, is wrenched from the swimming pool. Into the dumpster go the Mexican-church facade, the giant Buddha, the Egyptian tomb. By noon… the hundred-foot entranceway is stripped bare, and discarded icons litter the dance floor.” On this occasion, they were readying the locale for its next theme, Science Fiction, which would see the entranceway converted into an “intergalactic intestinal tract.”

Here are five of Area’s ambitious themes drawn from the namesake book.

Food

You hungry? Forget it. Unless, of course, you find a bloodied human gagged with food and her besmirched bra stuffed with vegetables appetizing. This party also featured a regular swimming pool, except filled with Alphabet Soup. In it a nonchalant waiter stood, waiting for something.

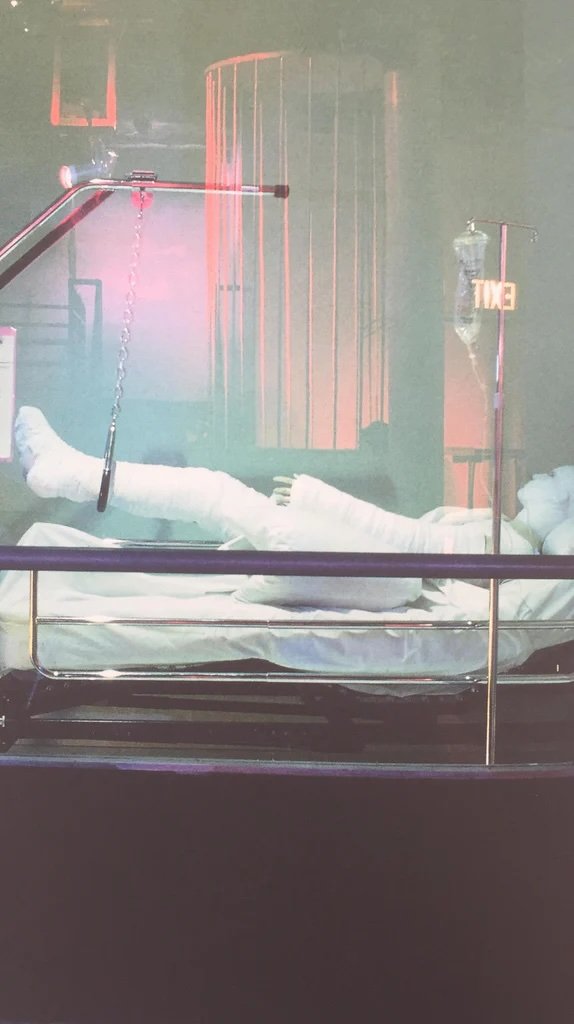

Confinement

Misery loves company, and the confinement theme was an exercise in sadism featuring sunken-eyed actors cowering in sterile bedroom corners. “I found [a cage] at a hospital supply company. The cage was for children in state hospitals and that was a horrific thing to think about.”—Jennifer Goode, Art Director.

Fellini

This party honoured filmmaker Federico Fellini and his indulgent, baroque predilections. Observe here guests eating seafood from the nude body of artist Magdalen Pierrakos. These eaters were apparently selected by the artist for their receding hairlines.

Science Fiction

…was an elaborate film starring you and your space fam. It was also maybe excruciating. ”The worst nightmare possible was Science Fiction—deciding what should go where, what was to be done, and then the feasibility of constructing it.”—Michael Staats, Art Department.

Natural History

It wasn’t only the structures inside the club that were notoriously elaborate, so too were the invitations. For Natural History, “we got about 2,000 eggs and Shawn made a drilling machine that drilled holes into them so we could blow the contents out of each one individually. Then ew put all the egg innards into maybe five or six huge garbage cans and loaded them into ur truck and drove them to the Salvation Army on Bowery. They were eating omelettes for days” — Jennifer Goode, Art Director.

A significant portion of streetwear in this high-powered digital climate is indebted to skate culture. But before the days of scrambling for the latest drop and cart jacking tantrums; before the Thrasher logo became synonymous with elite models on Instagram; before Vogue (yes, Vogue) ran a jarring campaign in 2016 called ‘Skateboarding Week’ — streetwear, skating and the internet weren’t so intimately entangled.

Sometime in the 50s, skating was born from surfers’ ennui with small, unsurfable waves. Its enthusiasts wore trousers and varsity jackets, or preppy sweaters. But skate style perhaps didn’t forge its own distinctive subculture until the 70s when the lax and nonchalant Cali-surf energy infiltrated skate culture.

When droughts of the mid-70s left Venice Beach swimming pools parched, the resultant culture of vertical transition skating was helmed by Dogtown locals, the Z-Boys. With it, Tony Alva rose to sartorial prominence for his woven headbands and slinky tube socks stuffed into Nike Blazers. Elsewhere, mate Jay Adams backed a signature look of thrashed Vans Authentics and long unkempt hair.

Cut to the 80s when pools were traded for ramps and the wavy aesthetic of VHS helmed by skaters-cum-videographers like The Bones Brigade (Stacy Peralta and George Powell), Vision (Brad Dorfman) and Santa Cruz ushered in more ostentatious flavours. Colours were many and varied and silhouettes more exaggerated. For the feet, OG Nike Air Jordans, Chuck Taylor's and Vans SK8-Hi were all on solid rotation. Also: World Industries.

The descriptor ‘irreverent’ is sometimes a lazy cliché assigned to anyone who doesn’t wear a suit or welcome hair brushing. But in the case of Steve Rocco, it fits. In the late 80s, the skater built World Industries with a brash DIY elixir of unbending confidence, schoolboy obnoxiousness and a very real thirst to engineer newness. The 90s were all about living large: hyper-baggy tees and baggier cartoon-y denim jeans falling over wide-set skate shoes (perhaps Etnies, Duffs KCKs or DC). It was also the year another seminal brand came into fruition: L.A. brand Fuct.

Fuct was constructed with a brazen, anti-establishment ethos that’s entirely befitting of an iconic skate company. Artist Erik Brunetti and skater Natas Kaupas birthed the seminal brand in 1990, its provocative graphic prints and pioneering modus unlike anything of its time.

Along with big brands like Nike investing a greater energy in skate, the noughties saw skating’s acute cross-pollination with high fashion. On the more calculated end of the spectrum, a Kenzo model carried a skateboard, the wrong way, down the runway for SS15. Supreme — whose life begun in 1994, a grim point in New York’s and indeed, skating’s economy — are a kind of counterpoint: a brand occupying a seemingly impenetrable high-low pocket; never dumbing down anything for the youth, the nucleus of their brand. Collaborations with Comme Des Garçons and (increasingly streetwise) Louis Vuitton happened, as did collaborations with Jeff Koons and Larry Clark; the latter and his film Kids, of course, a veritable corroboration of 90s youth.

Today, the spirit of Kids resides also in Fucking Awesome — most literally in a T-shirt featuring a young Chloe Sevigny, longtime friend of designer Jason Dill, but also in its overall gritty representation of youth and skating. Ever wanted to wear a t-shirt emblazoned with a dictator such as Adolf Hitler or Saddam Hussein? F.A. caters to such whims. Electing not to operate within the seasonal rhythm of the fashion industry, F.A. actually once ejected itself from business for a year when Jason Dill felt it was getting too popular. Dill makes stuff when he wants; when ideas are percolating. Like he told Vice, “Everybody has something and I have Fucking Awesome, sometimes.”

Elsewhere there’s the eponymous label of Mark Gonzales, or Gonz, or the guy named ‘Most Influential Skateboarder of All Time’ by Transworld in 2011. It’s quite wild to think the skater and father who hasn’t owned a smart phone in years has engineered a brand that the internet generation love so much. Or not, given his absolute pioneering street skating status, and lifelong art preoccupation.

Having outlived the dips, peaks and parched periods, skating’s influence can be seen in streetwear trends now more than ever. A culmination of 90s bravado and a move to swishier, glossier climes has paved ample space for disparate brands to share street style currency today.

Your Style Probably Owes a Lot to Skate Trends Through The Ages

editorial strategy / brand voice / writing / editorial strategy / brand voice / writing / editorial strategy / brand voi