Design: Chris Petrillo

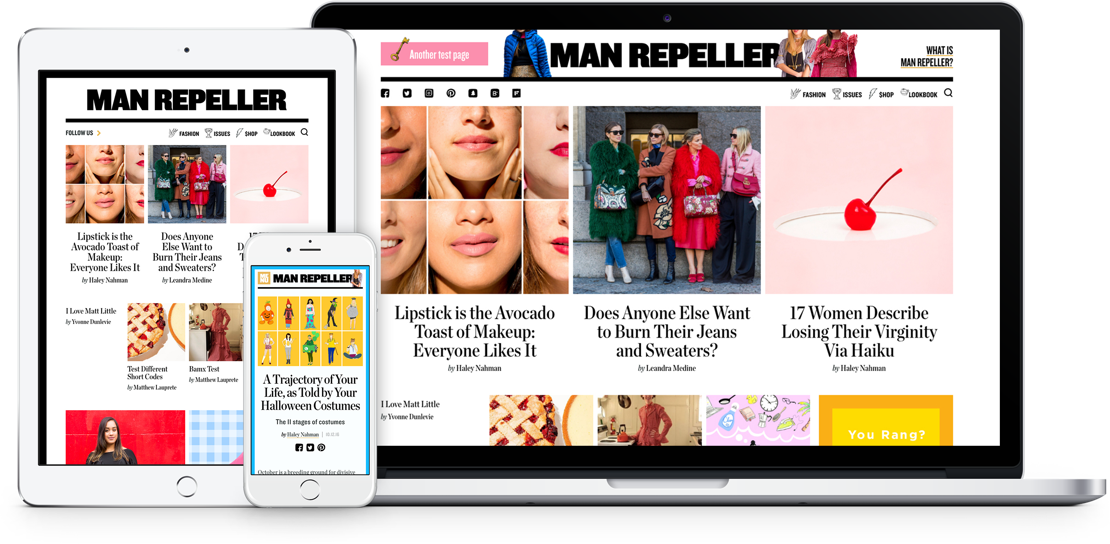

Man Repeller

Man Repeller was a digital editorial platform—and in fact, multi-media business—that beckoned a smart-but-silly, acerbic audience of women. It and Into the Gloss were the only two online publications a certain millennial woman cared to log onto between, say, 2010 and 2015.

Helmed by the singular Leandra Medine, the site celebrated emotionally generous writers with silly billy tendencies. I wrote about wellness for them.

pitching — writing — pitching — writing — pitching — writing — pitching — writing — pitching — writing — pitching — writing — pitching — writing — pitching — writing — pitching — writing — pitching — writing — pitching — writing — pitching — writing — pitching — writing — pitching — writing — pitching — writing — pitching — writing — pitching — writing — pitching — writing — pitching — writing — pitching — writing — pitching — writing — pitching — writing — pitching — writing — pitching — writing — pitching — writing — pitching — writing — pitching — writing — pitching — writing — pitching — writing — pitching — writing — pitching — writing — pitching — writing — pitching — writing — pitching — writing — pitching — writing — pitching — writing — pitching — writing — pitching — writing — pitching — writing — pitching — writing — pitching — writing — pitching — writing — pitching — writing — pitching — writing — pitching — writing — pitching — writing — pitching — writing — pitching — writing — pitching — writing — pitching — writing — pitching — writing — pitching — writing — pitching — writing — pitching — writing — pitching — writing — pitching — writing — pitching — writing — pitching — writing — pitching — writing — pitching — writing — pitching — writing — pitching — writing — pitching — writing — pitching — writing — pitching — writing — pitching — writing —

pitching — writing — pitching — writing — pitching — writing — pitching — writing — pitching — writing — pitching — writing — pitching — writing — pitching — writing — pitching — writing — pitching — writing — pitching — writing —

pitching — writing — pitching — writing — pitching — writing — pitching — writing — pitching — writing — pitching — writing — pitching — writing — pitching — writing — pitching — writing — pitching — writing — pitching — writing —

pitching — writing — pitching — writing — pitching — writing — pitching — writing — pitching — writing — pitching — writing — pitching — writing — pitching — writing — pitching — writing — pitching — writing — pitching — writing — pitching — writing — pitching — writing — pitching — writing — pitching — writing — pitching — writing — pitching — writing — pitching — writing — pitching — writing — pitching — writing — pitching — writing — pitching — writing — pitching — writing — pitching — writing — pitching — writing — pitching — writing — pitching — writing — pitching — writing — pitching — writing — pitching — writing — pitching — writing — pitching — writing — pitching — writing — pitching — writing — pitching — writing — pitching — writing — pitching — writing — pitching — writing — pitching — writing — pitching — writing — pitching — writing — pitching — writing — pitching — writing — pitching — writing — pitching — writing — pitching — writing — pitching — writing — pitching — writing — pitching — writing — pitching — writing — pitching — writing — pitching — writing — pitching — writing — pitching — writing — pitching — writing — pitching — writing — pitching — writing — pitching — writing — pitching — writing — pitching — writing — pitching — writing — pitching — writing — pitching — writing — pitching — writing — pitching — writing — pitching — writing — pitching — writing — pitching — writing — pitching — writing — pitching — writing — pitching — writing — pitching — writing — pitching — writing — pitching — writing — pitching — writing — pitching — writing — pitching — writing — pitching — writing — pitching — writing — pitching — writing — pitching — writing — pitching — writing — pitching — writing — pitching — writing — pitching — writing — pitching — writing — pitching — writing — pitching — writing —

What a Scary Diagnosis Taught Me About “Wellness”

I’ve always put a lot of pressure on myself to do a lot, very well and very fast. A few years ago, though, bossing myself around stopped working so well — not because I lowered my standards, but because I couldn’t seem to fulfill requests quickly enough. My body felt sluggish and strangely disengaged from my mind, which was regularly betraying my memories. Organizing my thoughts became laborious, like trying to befriend a very spoiled cat.

I started seeing doctors. Each time, I presented a growing buffet of symptoms: anxiety, gastrointestinal problems, poor sleep, allergies, food intolerances, acne, low energy, mood swings and weight fluctuations. Although everything seemed to be culminating at once, when I tried to trace their beginnings, things felt murky. Some of my symptoms, I realized, could be traced back several years, maybe even 10. But I’d always convinced myself they were simply byproducts of modern life. Stress will do that to a person, right?

Finally, after seeing 11 doctors over two years, I was diagnosed with an autoimmune disorder called Hashimoto’s thyroiditis. Autoimmune diseases are conditions wherein the body attacks its own healthy cells. In the case of Hashimoto’s, my body built up antibodies against my thyroid gland. The thyroid is a cute and butterfly-shaped control freak, regulating a person’s reaction to stress, muscle control, cognizance of hunger and satiety, heart and digestive function, sleep quality and more. As you can imagine, any disruption in its function can cause a variety of seemingly disconnected symptoms.

Doctors initially told me that my antibody count wasn’t high enough to warrant medication, but they said there were “lifestyle manipulations” I could make instead. Knowledge of this was, for lack of a less cheesy word, empowering. I dove into Google right away, which ushered me into a Facebook group of 76,000+ members called Hashimoto’s 411. The group was an informational conveyor belt with, on average, one post every hour.

In Hashimoto’s 411, I found a strangely comforting home. Vulnerable strangers posed questions to other vulnerable strangers. These other vulnerable strangers answered the questions with authority, based on their own unique collections of symptoms and strategies. I, too, have both asked and answered questions with authority on topics ranging from advice about iodine supplementation (controversial!), to conventional doctors (idiots, all of them), to which vegetables are easiest to digest (cooked, non-cruciferous ones low in salicylates). Each of my posts attracted 40+ replies, with empathetic peers pinging back suggestions like rubber bands, their oceanic compassion rippling through the feed.

At first, the exchanges felt sincere. But over time, they began to carry an air of paranoia, and I came to realize that they were also stoking something beyond comfort: fear. In this furtive corner of Facebook, I was learning to blindly appropriate fact and fiction about things like gluten intolerance, inflammation markers, coinfections and gut permeability. I construed the group as a reservoir of rich knowledge harboring the answers that would eventually heal me, forgetting that much of the content was subjective. I’d homogenized a complicated illness by lifting strangers’ strategies to treat my own assemblage of symptoms, denouncing food groups and erecting supplement spreadsheets.

One day, after reading a long thread that maligned synthetic ingredients in beauty products, suggesting they may cause Hashimoto flare-ups, I decided to discard all of my expensive makeup and skincare products in an impassioned fury. If indiscriminate internet users had taught me anything, it was that chemicals were bad, and that I was practically inviting illness into my life by buying them. After ushering in “clean” beauty counterparts, I then spent a designer dog price tag on supplements for “inner beauty” (known in some circles are “edible skincare”). The top shelf in my medicine cabinet had become ugly but interesting. But here’s the kicker: I still felt lousy. And I didn’t even have a puppy for my trouble.

The more links I clicked and tabs I opened, the more I felt my fear swell. Eventually, the fear would overpower even the initial symptoms I was experiencing. After a while, I realized I could scarcely differentiate my health anxiety from that of anyone else enmeshed in the wellness industrial complex. Pursuing alternative remedial strategies for a clinical disease might be different than habitually mining Goop for an adaptogen to raise your IQ or crystal therapies to shrink your pores (spoiler! both outcomes are impossible). But the governing principles of this industry — worth a quaint $3.7 trillion as of 2015 — can explain both schools of behavior.

Wellness assigns responsibility for health betterment to the individual. Have a dig around: A left-leaning health “solution” might plug the gaping hole in your soul engineered by the modern world, or it might turn out to be an actual solution. Either way, you’re crazy not to try. This is the rather humorous duality of hope and cynicism with which the average woman approaches wellness: Whether what ails you is pallid or pronounced, real or imagined, the answers are out there! You just have to spend every waking moment and all your savings to find them.

Which brings me to one of the most important health lessons this information-binge ultimately taught me: If you truly believe there are holes in your health, it’s wise to seek out a good doctor (possibly the integrative kind) before diving into the wild west of self-treating on the internet. A doctor who is thorough, curious and listens. I only just found mine — she’s lucky number 12. She ordered several comprehensive tests that were, yes, cripplingly expensive, but also revealed the mineral deficiencies that were directly causing my Hashimoto’s symptoms (primarily a paltry iodine supply, if you’re interested). She did this without once doubting the validity of my symptoms or arching a suspicious brow or wordlessly handing me a script for antidepressants. I now have supplements and strategies that work for my specific circumstances, and I’m using them and feeling better. I’ve still found it worthwhile to continue my own independent research — albeit, not with the all-consuming focus of yesteryear — but now I bring relevant theories to my appointments to be tested. Good doctors will advocate for patients who advocate for themselves.

Sadly, no amount of hope will turn backlit miscellanea into functional health strategies that serve you and your body and your own conglomeration of needs. Perhaps ironically, I’ve found that tirelessly drinking up the internet’s stream of health and wellness literature is not all that healthy.